Defining Information Architecture

We live in the days of big data. Never before in human history have we, as individuals, had access to more information. And frankly, never before have we dealt with this information in such a bad way.

- Most information systems are in a worse state than their paper counterparts were thirty years ago.

- Most information systems are vulnerable to intrusion, even when safety measures are top-notch.

- More information is lost day by day than we can hope to keep track off.

- More information is abused, traded, stolen and mishandled than ever before.

- More false information is spread on a daily basis, challenging our trust in our systems.

- etc. etc.

Now, while Information Architecture (IA) can help out here, it is not some magic formula. IA is a complex topic. It is a broad subject. IA has influence everywhere we look. And most of the time it isn’t really visible.

When was the last time you visited a website and said: “Wow, this really has bad Information Architecture”? Probably never.

Let’s start by looking at two things:

- Why do we need Information Architecture?

- How would we define Information Architecture?

Why do we need Information Architecture?

The Evolution of the Information Era

We were warned… in the 1970s Alvin Toffler introduced the phrase “information overload” in his book Future Shock. He stated that the increased rate of information production and the speed with which we would be exposed to this information would result in a reduction in the “signal to noise ratio” that we would not be able to handle. That was then, but this is now!

What did he mean? Let’s travel back in time a few years, shall we?

During the middle ages books were kept in monasteries, reproduced and maintained by monks who could write and only read by the few who could read. The information in those books was unique and carefully monitored.

Printing allowed for books to be reproduced in larger numbers and the information became available to a broader audience.

With the introduction of the digital age, a huge leap was taken. Now, the information was no longer connected to a physical entity. It was “out there” on your harddrive at first, on the web and in the cloud later. We still called it ebooks to make sense of it, but in reality the book was gone and the information liberated from its physical form.

We can add notes, metadata, reviews, opinions, cut, copy, paste the pieces we like and take it all out of context. Had you tried any of those things with a book in the middle ages, you would have swung from the gallows for sure!

The Problems of Digital Information

With the freedom of information we now have, we are faced with new challenges:

- The tool we use to absorb information has changed. The paper book has turned into an app or software program that manages media.

- The amount of media available to us means we are in need of an organization system that helps us find and retrieve a particular item.

- The use of multiple devices, each with their own capabilities and restraints, adds yet another layer of complexity.

- Interacting with others, each with their own organization system, compounds the complexity even further.

Hello Information Architecture

Remember iTunes? I deleted it several years ago. I was done with it. Useless piece of junk!

There was a time when I loved it though. I used it to organize my music collection. Great tool. There was no better one.

When I deleted it, iTunes had grown into a media platform with which I could:

- rip music, play music, organize my music collection,

- do the same for movies, podcasts, university courses, etc,

- buy, rent, stream, subscribe, share all of the above,

- use it with iPods, iPads, Apple Watch, Windows, etc.

iTunes went from being a tool I could use, to being what we call an ecosystem. And as software is written to solve specific problems and provide specific functionality, turning it into an ecosystem will hardly ever go well. Painful is that this happens to software that is successful at the start and slowly but surely becomes more clouded and more complicated until it grinds to a halt.

What is needed is a systematic, comprehensive, holistic approach to structuring information in a way that makes it easy to find and understand that information, regardless of the context, channel or medium being used. In other words, someone needs to step out of the product development cycle and look at the broader picture in an abstract way, in order to understand how it all fits together.

It is important to understand that we interact with digital products through the use of language:

- labels,

- menus,

- descriptions,

- tooltips,

- microcopy,

- content,

- visual elements.

All these elements work together in a system to create user understanding. Differences in language help define each system as a place where specific things can be done. For instance, a recipe app looks different from a car insurance app; as an insurance company you should take care that your app looks like an insurance app and not like a recipe app.

All these language elements are part of the Information Architecture. Like I said before, Information Architecture is everywhere in your ecosystems. And Information Architecture is all about language.

Definitions

In a previous article on the general definition of UX Design, I defined Information Architects as follows:

Information architects use the principles of information science, whether or not they learnt those principles formally, to help organizations present their data to users in a way that meets those user expectations and best helps them to complete their tasks.

Let’s look at some of the basic concepts we use in IA.

Information

Information separates my field from data and knowledge management.

- Data is facts and figures.

- Relational databases are highly structured data-storage systems.

- Knowledge is what’s inside people’s heads.

Information systems have no single right answer to questions. We are interested in information of all shapes and sizes:

- Websites,

- Documents,

- Software applications,

- Images,

- Metadata which describes all of the above,

- etc. etc.

Structuring, Organizing, and Labeling

With structuring we mean determining the appropriate levels of scale and detail of the information. And we look at how these chunks of information relate to one another.

Organizing means grouping them into categories, creating context for users to understand what they are looking at.

Labeling means establishing what to name things. We name categories and the navigational elements that point to them.

Finding and Managing

Finding what they are looking for is critical for your users. If this is hard, your system fails.

The people who manage all that information are important too.

Information Architecture will seek a balance between the user needs and the business goals. It is important to manage content efficiently and have policies and procedures in place to support this.

Art and Science

The practice of IA can never be reduced to pure number crunching. There is too much complexity and variance in the ecosystems involved.

Yet, IA also cannot be about the architect’s inner feelings alone. Good IA is about taking calculated risks with a healthy dose of intuition. We rely on experience and creativity to solve data supported problems and map out roads to their solution.

Moving to Good Information Architecture

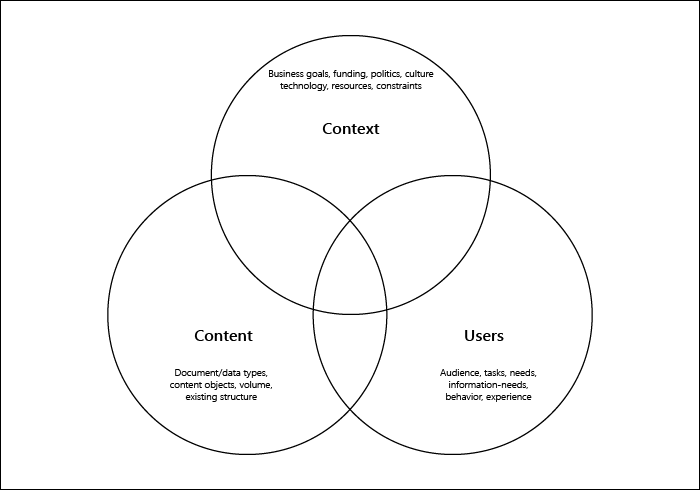

I have been using the term “ecosystem” to describe the digital systems we are dealing with. Every ecosystem consists of users, content and context. It is that simple and at the same time it is that complicated. We can visualize this in the following diagram.

- We need to understand the business goals behind the project and the resources available for design and implementation.

- We need to understand the nature and volume of the content that we have now and how that will evolve in the future, either up or down.

- Finally we must learn about the needs and behaviors of our target audiences.

Good IA design is based on all three areas, and none of these is static:

- Organizations will change their mission, vision, goals, politics, culture, and what not,

- Content will vary in quality, authority, popularity, strategic value, cost, and much more,

- Users will vary in attitude, demographics, tasks, needs, behavior, etc. etc.

Context

Your digital ecosystem exists first and foremost within your organization. It exists within your particular business model with its mission, goals, strategy, staff and much more. The IA should match this business model. The vocabulary and structure of your digital products is a major part of the conversation between your business, your customers and also your employees.

This is the first important step towards good IA. Your information architecture shows a snapshot of your organization’s mission, goals, etc. Do you really want that snapshot to be the same as that of your competitor? Your data structures probably are similar, but that is not all there is to IA. It’s the use of language that sets you apart; this sets the tone and represents your culture. It’s essential.

The key to success is understanding the business context and then align this with every outlet channel you use. You need to consider how these channels will overlap and interact with one another. Once again, you need to consider context.

Content

Content is everything that goes into your digital products. Text, images, media and all that good stuff.

The web was originally meant for communication. Of course these days we also use it for tasks and transactions. With regards to content, the following factors are important to map out:

- Ownership – who creates and owns the content.

- Format – as there are many many different ones.

- Structure – a tweet of 150 characters should be treated different than a 150 page manual.

- Metadata – to what extent does it exist and how accurate is it?

- Volume – how big is the system?

- Dynamism – how fast will the system grow, or what is the turnover rate?

Users

When we are talking about users, we are talking about people. How obvious as that may sound, it is often forgotten. System engineers suddenly assign attributes to large groups of people without variance for instance.

You will need a deep understanding of the people who will use your digital ecosystems.

The best way to get this deep understanding? Very simple… ask them!

In Conclusion

If you are still here, you must be serious about Information Architecture. Good! Some final words.

Where other design disciplines focus on the design of particular elements, IA is concerned with defining the semantic systems that these individual elements will be working in. It is unimportant whether your final product is an app, a website, some type of interface or a piece of software. The approach to Information Architecture remains the same.

In his book “Intertwingled”, Peter Morville calls out the dangers of low-level thinking when trying to design new (digital) products:

In the era of ecosystems, seeing the big picture is more important than ever, and less likely. It’s not simply that we are forced into little boxes by organizational silos and professional specialization. We like it in there. We feel safe. But we are not. This is no time to stick to your knitting. We must go from boxes to arrows. Tomorrow belongs to those who connect.

A high level, comprehensive understanding of the ecosystem can help ensure that its elements work together to present coherent experiences to users. This is where Information Architecture shines.

However, Information Architecture does not focus on high-level, abstract models alone. The design of products that are findable and understandable requires the creation of many low-level elements as well. Effective ecosystems strike a balance between structural coherence (high-level invariance) and suppleness (low-level flexibility and adaptability). Therefore, well-designed IA covers both, making sure you are solving the right problems.

In his book Introduction to General Systems Thinking, Gerald Weinberg uses the following brilliant story:

A minister was walking by a construction project and saw two men laying bricks.

“What are you doing?”, he asked the first.“I’m laying bricks”, the man answered gruffly.

“And you?”, he asked the other,

“I am building a cathedral!”, came the happy reply.The minister was agreeably impressed with this man’s idealism and sense of participation in God’s Grand Plan. He composed a sermon on the subject and returned the next day to speak to the inspired bricklayer. Only the first man was at work.

“Where’s your friend?”, asked the minister.

“He got fired.”

“How terrible. Why?”

“He thought we were building a cathedral, but we’re building a garage.”

So, always ask yourself: am I building a cathedral or a garage? The difference is important and it is difficult to tell when you are focused on laying bricks.

Until next time.